A few years back, Denise Minger instantly rose to fame in the Low-Carb and Paleo diet circles shortly after publishing a blog post criticizing the chapter describing the findings from the China-Cornell-Oxford Project in the book, The China Study, written by Dr. T. Colin Campbell.1 This blog post was very welcomed by proponents of these diets as it provided them with a reference which they used to attempt to use refute much criticism they had been receiving for promoting a diet rich in animal foods.

A few years back, Denise Minger instantly rose to fame in the Low-Carb and Paleo diet circles shortly after publishing a blog post criticizing the chapter describing the findings from the China-Cornell-Oxford Project in the book, The China Study, written by Dr. T. Colin Campbell.1 This blog post was very welcomed by proponents of these diets as it provided them with a reference which they used to attempt to use refute much criticism they had been receiving for promoting a diet rich in animal foods.One reason Minger’s critique likely received much attention, was that unlike other individuals who have attempted to criticize the China Study, rather than making her intention of defending a diet rich in animal foods obvious, Minger attempted to give readers a false impression that if anything she was bias towards a plant-based diet. Minger’s intentions became somewhat apparent when Paleo diet proponent Richard Nikoley posted an e-mail that he received from Minger on his blog.2 The contents of this e-mail made it obvious that Minger had been sending e-mails to proponents of Low-Carb and Paleo diets, suggesting that they cite her blog post as "ammo" to shoot down "vegans" who cite The China Study. The language used by Minger in the e-mail, such as the statement “Of course, they aren't”, in reference to whether animal foods are linked to chronic diseases, suggested the likelihood of confirmation bias in favor of downplaying the harms of animal foods. This raises the question as to whether it was her intention to simply downplay Dr. Campbell’s work, rather than producing an honest review.

As described previously by Plant Positive, and myself, there were a number of serious concerns with Minger’s interpretations of the data from the China Study which further casted doubt on her true intentions. One particular example was Minger's attempt to attribute the association between fat intake, a marker of animal food intake, and an increased risk of breast cancer mortality in the China Study to the consumption of "hormone-injected livestock".3 The fact that the mortality data that Minger examined was from the early to mid-1970s, a time when the use of hormone injections was not exactly widely practiced throughout rural China casts serious doubt on this claim. Furthermore, it is important to consider that the time lag between exposure to a causal agent and when breast cancer becomes life threatening is more than often several decades. For example, the greatest risk of excess death from radiation-related solid cancers, such as breast cancer among the atomic bomb survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was more than half a century after exposure.4 It is therefore likely that most of the dietary related deaths from breast cancer that occurred in the early 1970s would more likely to have been caused by the diets consumed several decades earlier, likely even before hormone injections was used to any meaningful extent in China. This provides further suggestive evidence that Minger was merely trying to downplay the evidence of the harms of animal foods, rather than producing an honest review.

As described previously by Plant Positive, and myself, there were a number of serious concerns with Minger’s interpretations of the data from the China Study which further casted doubt on her true intentions. One particular example was Minger's attempt to attribute the association between fat intake, a marker of animal food intake, and an increased risk of breast cancer mortality in the China Study to the consumption of "hormone-injected livestock".3 The fact that the mortality data that Minger examined was from the early to mid-1970s, a time when the use of hormone injections was not exactly widely practiced throughout rural China casts serious doubt on this claim. Furthermore, it is important to consider that the time lag between exposure to a causal agent and when breast cancer becomes life threatening is more than often several decades. For example, the greatest risk of excess death from radiation-related solid cancers, such as breast cancer among the atomic bomb survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was more than half a century after exposure.4 It is therefore likely that most of the dietary related deaths from breast cancer that occurred in the early 1970s would more likely to have been caused by the diets consumed several decades earlier, likely even before hormone injections was used to any meaningful extent in China. This provides further suggestive evidence that Minger was merely trying to downplay the evidence of the harms of animal foods, rather than producing an honest review.

Given Denise Minger’s misleading blog posts, naturally I was more concerned than interested to see what sort of take home message Minger would be attempting to provide readers of her recently published book, Death By Food Pyramid. I have therefore decided to review a number of the key sections of the book to help readers to decide whether to purchase and incorporate the dietary advice in this book.

The IMPACT of the Food Pyramid

|

| The original USDA Food Pyramid from 1992 |

Although it may be fair to suggest that the federal dietary guidelines can be considered as a lost opportunity to save additional lives, evidence does not suggest that the Food Pyramid promoted a diet that would have increased the risk of dietary related deaths compared to the cholesterol-rich diet consumed by Americans in earlier decades. For example, numerous studies have found that in a number of nations, including the United States, large reductions in serum cholesterol, largely as the result of displacing the proportion of saturated fat in the diet with other sources of energy can explain a significant portion of the decline in coronary heart disease mortality. These large declines generally occurred in order of the nations that were earlier to embrace the lipid hypothesis and reduce the intake of animal fat. For example, this decline began in the late 1960s in the United States, Finland, Australia and New Zealand, but not until a decade later in the United Kingdom which had been distracted by John Yudkin's sugar hypothesis and much slower to embrace the lipid hypothesis.6 In the former communist nations of Eastern Europe, this decline did not occur until the 1990s, following the abolishment of communist subsidies on meat and animal fats after the collapse of the Soviet Union.6

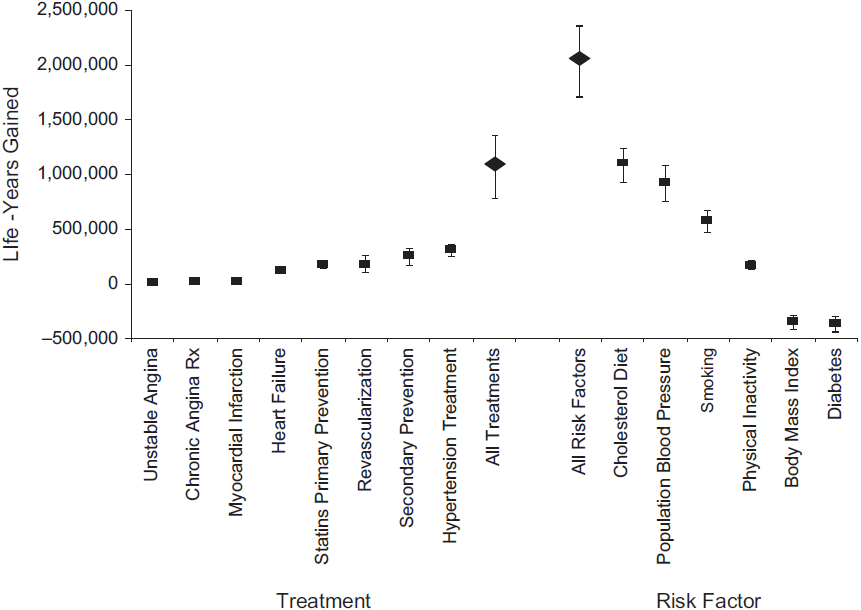

Although Minger notes this observed decline in mortality in the United States in her book, she suggests that it can more likely be explained by the reduction in smoking prevalence, rather than the displacement of saturated fat with other sources of energy, such as omega-6 polyunsaturated fats and carbohydrate. Minger however failed to provide any data demonstrating what portion of the decline in mortality could be attributed to changes in smoking prevalence and diet/serum lipids. The IMPACT CHD mortality model incorporates among the highest quality data available for risk factors and treatments to help determine how individual risk factors and treatments have contributed to changes in coronary heart disease mortality of a given population. The fact that the prediction of change in coronary heart disease mortality calculated by the IMPACT model has been demonstrated to be largely comparable with the actual change in mortality in nations throughout North America, Northern, Southern, Eastern and Western Europe, South-East Asia, Africa, Australasia and the Middle East provides confidence in the validity of this model.7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21

It should be noted that the use of the IMPACT model has made it clear that in those nations which experienced the most dramatic declines in heart disease mortality in the world, such as Finland and the former communist nations of Eastern Europe, large dietary induced declines in serum cholesterol has typically explained a very significant portion of the decline.8 9 10 22 23 The same can be said for the increases in serum cholesterol as the result of an increase in intake of cholesterol and saturated fat, and the surge in heart disease mortality among a number of populations, such as Beijing.17 19 These findings are also supported by earlier studies.6 For example, in 1989 Epstein examined the changes in coronary heart disease mortality in 27 countries during the previous 10 to 25 years, noting that:24

In almost all of the countries with major falls or rises in CHD mortality, there are, respectively, corresponding decreases or increases in animal fat consumption...

Epstein also noted that during this period the prevalence of smoking among women remained largely unchanged or increased in most nations, and that therefore changes in smoking prevalence was unable to explain the large differences in the rate of decline between countries and sexes.24

The IMPACT model found that in the United States between the years of 1980 and 2000, a time at which coronary heart disease mortality was reduced by about half, the decline in serum cholesterol, largely due to changes in diet, could explain approximately 24% of this reduction, compared to only about 12% for the decline in smoking prevalence (Fig. 1).7 22 Considering that coronary heart disease has been the leading cause of death in the United States, as well as many other nations for the best part of a century, if anything, a more appropriate title for Minger's book would be "Saved By Food Pyramid".25

Worst Case Scenario for the McGovern Report: Denise Minger

In the chapter Amber Waves of Shame, Denise Minger attempts to explain about the implementation of the Dietary Goals for the United States of 1977, also known as McGovern Report. This report has been considered by many as laying a cornerstone for the forthcoming USDA guidelines. In this chapter, Minger also describes how the egg, meat, milk, salt and sugar industries attempted to hijack the report due to the nature of the recommendations to limit these foods, referencing a video on this topic by Dr. Michael Greger which can be viewed below. It comes as no surprise that Minger cited this video but chose to neglect many of the hundreds of studies cited throughout Dr. Greger's series of videos that cast significant doubt on her own dietary recommendations.

In an attempt to criticize the science supporting the McGovern Report, Minger focuses on a publication from the American Society for Clinical Nutrition (ASCN) expert committee, published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition in 1979, which critically examined the evidence for each of the foods and nutrients that the McGovern Report recommended limiting. Minger states that there was significant disagreement among the ASCN panel regarding the causal association between dietary cholesterol, saturated fat and heart disease. Nevertheless, the panel gave the strength of evidence of a causal association for dietary cholesterol and saturated fat combined a score of 73 out of 100, which was considered “rather high”. Because the score of each of the panelists contributed equally to the overall score, this rather high score suggests that very few of the panelists were in significant disagreement with the diet-heart hypothesis. For dietary cholesterol and saturated fat considered separately, the scores were a little lower, which was suggested to be due to the nature of these two nutrients being highly correlated, making it difficult to determine which contributes more to atherosclerotic heart disease.26 In comparison, virtually all of the panelists considered the evidence linking carbohydrate (ie. sugar) to heart disease as being “extremely weak”, scoring it only 11 out of 100.26 This fact is however largely neglected by Minger despite discussing the potential adverse effects of sugar on heart health in this book.

Dr. Michael Greger on the McGovern Report

In an attempt to criticize the science supporting the McGovern Report, Minger focuses on a publication from the American Society for Clinical Nutrition (ASCN) expert committee, published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition in 1979, which critically examined the evidence for each of the foods and nutrients that the McGovern Report recommended limiting. Minger states that there was significant disagreement among the ASCN panel regarding the causal association between dietary cholesterol, saturated fat and heart disease. Nevertheless, the panel gave the strength of evidence of a causal association for dietary cholesterol and saturated fat combined a score of 73 out of 100, which was considered “rather high”. Because the score of each of the panelists contributed equally to the overall score, this rather high score suggests that very few of the panelists were in significant disagreement with the diet-heart hypothesis. For dietary cholesterol and saturated fat considered separately, the scores were a little lower, which was suggested to be due to the nature of these two nutrients being highly correlated, making it difficult to determine which contributes more to atherosclerotic heart disease.26 In comparison, virtually all of the panelists considered the evidence linking carbohydrate (ie. sugar) to heart disease as being “extremely weak”, scoring it only 11 out of 100.26 This fact is however largely neglected by Minger despite discussing the potential adverse effects of sugar on heart health in this book.

Minger quotes several selected sentences from the paper on dietary fat and heart disease by ASCN panelist Charles J. Glueck regarding the failure of several diet-heart trials to produce unequivocal supportive evidence, suggesting as if Glueck concluded that there was scant evidence supporting the diet-heart hypothesis. This however was not the case. Glueck actually indicated that while it can be considered that there may not have been unequivocal evidence supporting the diet-heart hypothesis, there was some strong suggestive evidence. In fact, in the paper Minger cites, Glueck described why the failure of the diet-heart trials to produce statistical significant findings does not necessarily negate the hypothesis:27

These failures could have been due to the short duration of the studies, the age of subjects at inception of the studies, or to the inadequacy of the changes in plasma lipids so produced.

In a different paper published in the same issue of the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Glueck cited several lines of strong suggestive evidence supporting the diet-heart hypothesis. Notably, Glueck stated:28

Animal studies, particularly in subhuman primates, reveal an unequivocal causal relation between dietary cholesterol or saturated fat, plasma cholesterol levels and development or regression of atherosclerosis

Considering that there is “unequivocal causal” evidence from experiments on nonhuman primates, naturally this would be of considerable concern for humans. If a similar harmful effect would to be shown for a food additive, especially at intakes even lower than that typically consumed in developed nations, there is little doubt that it would be banned almost immediately. Furthermore, in this same paper, without expressing significant disagreement, Glueck quoted the conclusions of a review of the epidemiological evidence by Jerimiah Stamler, one of the expert advisors for the McGovern Report:28

…there is every reason to conclude-based on all seven criterias set forth-that the epidemiologic associations among dietary lipids serum cholesterol and CHD incidence represent etiologically significant relationships. In the multifactorial causation of this disease at least four major factors are operative; diet high in cholesterol and saturated fat, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension and cigarette smoking. However, since the data from both animal and human studies indicate that high blood pressure and cigarette smoking are minimally significant in the absence of the nutritional metabolic prerequisites for atherogenesis, it is further reasonable and sound to designate ‘rich diet’ as a primary, essential, and necessary cause of the current epidemic of premature atherosclerotic disease ranging in the Western industrialized countries.

As has been the case for smoking, there has never been, and never will likely be a definitive trial which tests the diet-heart hypothesis. Indeed, the few smoking cessation trials that have been carried out have failed to produce statistically significant findings for lung cancer mortality. Some of these trails even produced paradoxical findings, including non-significant increased rates of mortality from lung cancer and other cancers in the cessation group.29 30 Similar to the diet-heart trials, there are however plausible explanations as to why these trials failed to demonstrate significant findings for the benefits of smoking cessation. Such explanations include an insufficient duration of study period, and only modest differences in risk factors, points that Glueck noted as limitations of the trails testing the diet-heart hypothesis.29 30 This illustrates why it is critical to consider the totality of evidence, as negative findings from certain lines of evidence, even when normally considered to be at the top of the hierarchy of evidence does not necessarily negate a hypothesis. In other words, the lack of unequivocal evidence should not necessarily prevent federal agencies from recommending lifestyle changes to the public. This point was made clear by Senator George McGovern when he responded to criticism of the report, asserting that:31

I would only argue that Senators don´t have the luxury that a research scientist does of waiting until every last shred of evidence is in.

Minger also attempts to downplay the McGovern Report by taking the statements made by members of the McGovern Committee out of context. For example, Minger focuses on the statements of McGovern Committee member Chris Hitt who believed that even in the worst case scenario, that at the very least "the goals were safe, that there were no risks". Minger then takes this statement out of context to suggest as if the committees opinion of the likely effectiveness of the guidelines had more or less became “at least this probably won’t kill everybody”[p.43]. This statement, which suggests that the guidelines are not only ineffective, but are potentially dangerous, is clearly not what Chris Hitt stated, and is a far stretch from the opinion of committee as a whole.

Although Minger would try to have readers believe that a significant portion of the experts at the time were not in favor of the diet-heart hypothesis, evidence strongly suggests otherwise. As pointed out by Plant Positive in his new series of videos, in December 1976, just before the publication of first edition of the dietary goals, Dr. Kaare R. Norum conducted a survey to confirm how supportive the experts in the field were of the validity of the diet-heart and lipid hypotheses. Out of 211 epidemiologists, nutritionists and geneticists who received the survey, 193 recipients from 23 different countries responded.32 The list of surveyed recipients was considered to have included virtually every prominent researcher in the field from the time.33 As a result of this survey, Norum asserted that:

Although Minger would try to have readers believe that a significant portion of the experts at the time were not in favor of the diet-heart hypothesis, evidence strongly suggests otherwise. As pointed out by Plant Positive in his new series of videos, in December 1976, just before the publication of first edition of the dietary goals, Dr. Kaare R. Norum conducted a survey to confirm how supportive the experts in the field were of the validity of the diet-heart and lipid hypotheses. Out of 211 epidemiologists, nutritionists and geneticists who received the survey, 193 recipients from 23 different countries responded.32 The list of surveyed recipients was considered to have included virtually every prominent researcher in the field from the time.33 As a result of this survey, Norum asserted that:

Almost all agreed that there is a connection between diet and the development of CHD, between diet and plasma lipoprotein levels, and between plasma cholesterol and the development of CHD.

It is clear that Minger is trying to give the reader the false impression that the McGovern Committee, the ASCN expert committee, and a large portion of experts in this field felt that the guidelines of the McGovern Report, particularly the guidelines regarding the restriction of cholesterol and saturated fat were not evidence based by taking selected statements made by a number of these experts out of context. These tactics were perhaps used in order to give the reader the false impression that, even from the beginning, the federal guidelines have never been evidence based, providing momentum for the rest of her book. As can be seen from the table below based on Norum's survey, the impression that Minger attempts to provide the reader of the expert opinion of the time should be considered as misleading.

Failing to Meet Her Own Demands

In Death By Food Pyramid, Denise Minger criticizes the federal dietary guidelines, such as those to restrict dietary cholesterol and saturated fat, not so much due to a lack of high quality suggestive evidence, but due to the lack of unequivocal evidence. At the same time, Minger fails to provide any unequivocal evidence to support her own dietary recommendations, recommendations that she seems to suggest should be adopted into the federal guidelines. Minger also suggests that observational studies help little to determine causation when reviewing studies that cast doubt on her recommendations, yet often cites observational studies as the primary line of evidence to support her own recommendations. The fact that Minger is so demanding of the quality of evidence for those federal dietary guidelines that she disagrees with, while having far looser criteria for evidence supporting her favored hypotheses suggests the likelihood of denialism.

Although there is definitely room for significant improvements in the federal guidelines, Denise Minger’s suggestions for improvements are a step in the wrong direction. It is for this reason that it is not possible to recommend this book to anyone interested in health. In conclusion, it appears that Minger is more interested in promoting shoddy science than those who designed the food pyramid.